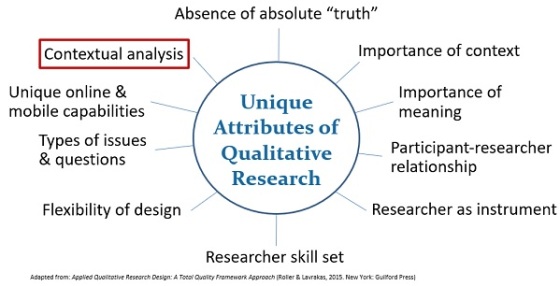

One of the 10 unique or distinctive attributes of qualitative research is contextual, multilayered analysis. This is a fundamental aspect of qualitative research and, in fact, plays a central role in the unique attributes associated with data generation, i.e., the importance of context, the importance of meaning, the participant-researcher relationship, and researcher as instrument —

“…the interconnections, inconsistencies, and sometimes seemingly illogical input reaped in qualitative research demand that researchers embrace the tangles of their data from many sources. There is no single source of analysis in qualitative research because any one research event consists of multiple variables that need consideration in the analysis phase. The analyzable data from an in-depth interview, for example, are more than just what was said in the interview; they also include a variety of other considerations, such as the context in which certain information was revealed and the interviewee–interviewer relationship.” (Roller & Lavrakas, pp. 7-8)

The ability — the opportunity — to contextually analyze qualitative data is also associated with basic components of research design, such as sample size and the risk of relying on saturation which “misguides the researcher towards prioritizing manifest content over the pursuit of contextual understanding derived from latent, less obvious data.” And the defining differentiator between a qualitative and quantitative approach, such as qualitative content analysis in which it is “the inductive strategy in search of latent content, the use of context, the back-and-forth flexibility throughout the analytical process, and the continual questioning of preliminary interpretations that set qualitative content analysis apart from the quantitative method.”

There are many ways that context is integrated into the qualitative data analysis process to ensure quality analytical outcomes and interpretations. Various articles in Research Design Review have discussed contextually grounded aspects of the process, such as the following (each header links to the corresponding RDR article).

“Although there is no perfect prescription for every study, it is generally understood that researchers should strive for a unit of analysis that retains the context necessary to derive meaning from the data. For this reason, and if all other things are equal, the qualitative researcher should probably err on the side of using a broader, more contextually based unit of analysis rather than a narrowly focused level of analysis (e.g., sentences).”

“How we use our words provides the context that shapes what the receiver hears and the perceptions others associate with our words. Context pertains to apparent as well as unapparent influences that take the meaning of our words beyond their proximity to other words [or] their use in recognized terms or phrases…”

“No one said that qualitative data analysis is simple or straightforward. A reason for this lies in the fact that an important ingredient to the process is maintaining participants’ context and potential multiple meanings of the data. By identifying and analyzing categorical buckets, the researcher respects this multi-faceted reality and ultimately reaps the reward of useful interpretations of the data.”

“Although serving a utilitarian purpose, transcripts effectively convert the all-too-human research experience that defines qualitative inquiry to the relatively emotionless drab confines of black-on-white text. Gone is the profound mood swing that descended over the participant when the interviewer asked about his elderly mother. Yes, there is text in the transcript that conveys some aspect of this mood but only to the extent that the participant is able to articulate it.”

“Unlike the transcript, the recording reminds the researcher of how and when the atmosphere in the [focus] group environment shifted from being open and friendly to quiet and inhibited; and how the particular seating arrangement, coupled with incompatible personality types, inflamed the atmosphere and seriously colored participants’ words, engagement, and way of thinking.”

page of his

page of his