Qualitative and quantitative research designs require the researcher to think carefully about how and how many to sample within the population segment(s) of interest related to the research objectives. In doing so, the researcher considers demographic and cultural diversity, as well as other distinguishing characteristics (e.g., usage of a particular service or product) and pragmatic issues  (e.g., access and resources). In qualitative research, the number of events (i.e., the number of in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, or observations) and participants is often considered at the early design stage of the research and then again during the field stage (i.e., when the interviews, discussions, or observations are being conducted). This two-stage approach, however, can be problematic. One reason is that giving an accurate sample size prior to data collection can be difficult, particularly when the researcher expects the number to change as the result of in-the-field decisions.

(e.g., access and resources). In qualitative research, the number of events (i.e., the number of in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, or observations) and participants is often considered at the early design stage of the research and then again during the field stage (i.e., when the interviews, discussions, or observations are being conducted). This two-stage approach, however, can be problematic. One reason is that giving an accurate sample size prior to data collection can be difficult, particularly when the researcher expects the number to change as the result of in-the-field decisions.

Another potential problem arises when researchers rely solely on the concept of saturation to assess sample size when in the field. In grounded theory, theoretical saturation

“refers to the point at which gathering more data about a theoretical category reveals no new properties nor yields any further theoretical insights about the emerging grounded theory.” (Charmaz, 2014, p. 345)

In the broader sense, Morse (1995) defines saturation as “‘data adequacy’ [or] collecting data until no new information is obtained” (p. 147).

Reliance on the concept of saturation presents two overarching concerns: 1) As discussed in two earlier articles in Research Design Review – Beyond Saturation: Using Data Quality Indicators to Determine the Number of Focus Groups to Conduct and Designing a Quality In-depth Interview Study: How Many Interviews Are Enough? – the emphasis on saturation has the potential to obscure other important considerations in qualitative research design such as data quality; and 2) Saturation as an assessment tool potentially leads the researcher to focus on the obvious “new information” obtained by each interview, group discussion, or observation rather than gaining a deeper sense of participants’ contextual meaning and more profound understanding of the research question. As Morse (1995) states,

“Richness of data is derived from detailed description, not the number of times something is stated…It is often the infrequent gem that puts other data into perspective, that becomes the central key to understanding the data and for developing the model. It is the implicit that is interesting.” (p. 148)

With this as a backdrop, a couple of recent articles on saturation come to mind. In “A Simple Method to Assess and Report Thematic Saturation in Qualitative Research” (Guest, Namey, & Chen, 2020), the authors present a novel approach to assessing sample size in the in-depth interview method that can be applied during or after data collection. This approach is born from quantitative research design and indeed the authors reference concepts such as “power calculations,” p-values, and odds ratios. When used during data collection, the qualitative researcher applies the assessment tool by calculating the “saturation ratio,” i.e., the number of new themes derived from a specified “run” of interviews (e.g., two) divided by the “base” number of “unique themes,” i.e., themes identified at the initial stage of interviewing. Importantly, the rationale for this approach is lodged in the idea that “most novel information in a qualitative dataset is generated early in the process” (p. 6) and indeed “the most prevalent, high-level themes are identified very early on in data collection, within about six interviews” (p. 10).

This perspective on saturation assessment is balanced by two other recent articles – “To Saturate or Not to Saturate? Questioning Data Saturation as a Useful Concept for Thematic Analysis and Sample-size Rationales” (Braun & Clarke, 2019) and “The Changing Face of Qualitative Inquiry” (Morse, 2020). In these articles, the authors express similar viewpoints on at least two considerations pertaining to sample size and the use of saturation in qualitative research. The first has to do with the importance of meaning1 and the idea that finding meaning requires the researcher to actively look for contextual understandings and to have good analytical skills. For Braun and Clarke, “meaning is not inherent or self-evident in data” but rather “meaning requires interpretation” (p. 10). In this way, themes do not simply pop up during data collection but rather are the result of actively conducting an analysis to construct an interpretation.

Morse talks about the importance of meaning from the perspective that saturation hampers meaningful insights by restricting the researcher’s exploration of “new data.” Instead of using “redundancy as an indication for broadening the sample, or wondering why this replication occurs,” the researcher stops collecting data leading to a “more shallow” analysis and “trivial” results (p. 5).

The second consideration related to saturation discussed in both the Braun and Clarke and Morse articles is the idea that sample size determination requires a nuanced approach, with careful attention given to many factors related to each project. For researchers using reflexive thematic analysis, Braun and Clarke mention 10 “intersecting aspects,” including “the breadth and focus of the research question,” population diversity, “scope and purpose of the project,” and “pragmatic constraints” (p. 11). In a similar manner, Morse includes on her list of eight “criteria” such items as “the complexity of the questions/phenomenon being studied,” “the scope of inquiry,” and “variation of participants” (p. 5).

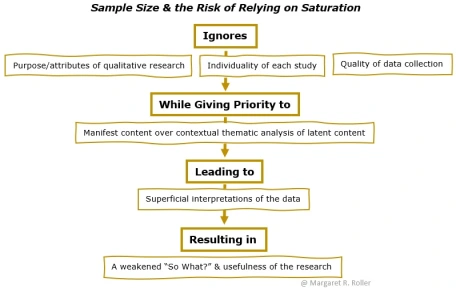

The potential danger of relying on saturation to establish sample size in qualitative research is multifold. The articles discussed here, and the image above, highlight the underlying concern that a reliance on saturation: 1) ignores the purpose and unique attributes of qualitative research as well as the individuality of each study, along with a variety of quality considerations during data collection, which 2) misguides the researcher towards prioritizing manifest content over the pursuit of contextual understanding derived from latent, less obvious data, which 3) leads to superficial interpretations and 4) ultimately results in less useful research.

1 Sally Thorne (2020) shares this perspective on the importance of meaning in her discussion of pattern recognition in qualitative analysis – “…qualitative research is meant to add value to a field rather than simply reporting what we can detect about it that has the qualities of a pattern… it should clearly add to our body of understanding in some meaningful manner.” (p. 2)

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing Grounded Theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Guest, G., Namey, E., & Chen, M. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLOS ONE, 15(5), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232076

Morse, J. (2020). The changing face of qualitative inquiry. International Journal for Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920909938

Morse, J. M. (2015). Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research, 25(9), 1212–1222. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Thorne, S. (2020). Beyond theming : Making qualitative studies matter. Nursing Inquiry, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12343

Helpful information for researchers and students who opt to undertake qualitative study. I have learned much more from this information and I like qualitative research

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love the discussion!

LikeLiked by 1 person