John Tarnai, Danna Moore, and Marion Schultz from Washington State University presented a poster at the 2011 AAPOR conference in Phoenix titled, “Evaluating the Meaning of Vague Quantifier Terms in Questionnaires.” Their research began with the premise that “many questionnaires use vague response terms, such as ‘most’, ‘some’, ‘a few’ and survey results are analyzed as if these terms have the sa me meaning for most people.” John and his team have it absolutely right. Quantitative researchers routinely design their scales while casting only a casual eye on the obvious subjectivity – varying among respondents, analytical researchers, and users of the research – built into their structured measurements.

me meaning for most people.” John and his team have it absolutely right. Quantitative researchers routinely design their scales while casting only a casual eye on the obvious subjectivity – varying among respondents, analytical researchers, and users of the research – built into their structured measurements.

One piece of the Tarnai, et al research asked residents of Washington State about the likelihood that they will face “financial difficulties in the year ahead.” The question was asked using a four-point scale – very likely, somewhat likely, somewhat unlikely, and very unlikely – followed by a companion question that asked for a “percent from 0% to 100% that estimates the likelihood that you will have financial difficulties in the year ahead.” While the results show medians that “make sense” – e.g., the median percent associated with “very likely” is 80%, the median for “very unlikely” is 0% – it is the spread of percent associations that is interesting. For instance, some people who answered “very likely” also said that there was a 100% chance of financial difficulties but other people who answered “very likely” stated that the likelihood of being in financial difficulty was less than 50%. And the respondents who responded “somewhat likely” indicated that their chance of facing financial difficulty was anywhere from 100% to as low as 0%! So what on earth does “somewhat likely” actually mean?

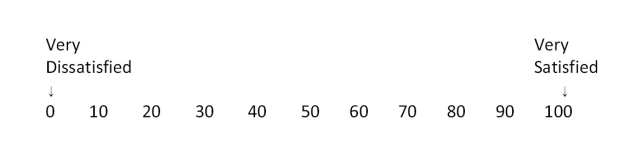

I returned from the AAPOR conference and found in my mailbox a customer satisfaction survey from Amtrak. This questionnaire is comprised of 36 rating questions all but three of which involve 11-point scales that look something like this:

So here is a question design that actually defines the vague term “very” by telling the respondent that “very satisfied” is equal to 100 and “very dissatisfied” is equal to 0. The problem of vague terms looks like it’s solved. Or is it? As a respondent I found the design disconcerting. It almost felt like a double-barreled question asking, on the one hand, if I was satisfied or dissatisfied with the train service and, on the other hand, if I was 100% satisfied, 90%, 20%? Frankly, I was stopped in my tracks (pun intended).

So here is a question design that actually defines the vague term “very” by telling the respondent that “very satisfied” is equal to 100 and “very dissatisfied” is equal to 0. The problem of vague terms looks like it’s solved. Or is it? As a respondent I found the design disconcerting. It almost felt like a double-barreled question asking, on the one hand, if I was satisfied or dissatisfied with the train service and, on the other hand, if I was 100% satisfied, 90%, 20%? Frankly, I was stopped in my tracks (pun intended).

Maybe there is some value in the vagueness of our terms, at least from the standpoint of the respondent. Maybe it is a good thing allowing respondents to answer from their own understanding of terms, saving them the anguish of fixing their satisfaction to a metric. But if the researcher is to have any hope of providing usable data to the client, attention has to be paid to clarifying survey responses. After all, wouldn’t you want to know if the finding that 90% of your customers are “very likely” to buy from you again really means there is a 50-50 chance of a repeat purchase?

I agree. ‘Very likely’ might mean the same thing to one respondent as ‘somewhat likely’ means to another, yet as researchers we treat them as completely separate responses.

But in quantitative research I always report the respondents in aggregate–so the percentage scale would get reported as a median, which as the article states, still lines up with the Likert scale. So is it really better? Whether the data is ‘80% of respondents are ‘very likely’ to consider XX’ or ‘The median likelihood of consideration of respondents is 75%’ it seems there is still a big lack of clarity.

LikeLike

I agree with the case in point in your article Margaret, but do you have any suggestions to improve those scales you referenced? It seems like they are very commonplace in the industry, was just wondering if you had any recommendations/thoughts?

LikeLike

Thanks, George, for the question. I actually like how the researchers at WA State handled it, i.e., by asking the percentage question. And pre-testing via cognitive interviewing would help define those terms, at least for that particular respondent type. It also helps to make distinctions in terms as clear as possible, e.g., I have always found a scale that uses “extremely satisfied” and “very satisfied” or “excellent” and “very good” to be incredibly confusing—impossible for the respondent to know the difference and even more impossible for the researcher to analyze.

LikeLike